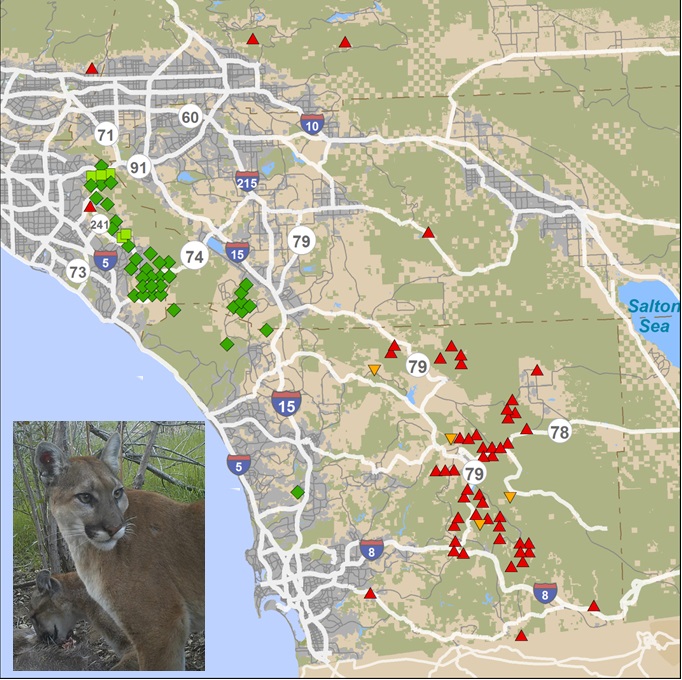

The mountain lions of southern California are hemmed in on all sides. In one place a 10-lane highway divides mountain lion habitat. All that development is particularly difficult on a species with such a large home range.

The mountain lions of southern California are hemmed in on all sides. In one place a 10-lane highway divides mountain lion habitat. All that development is particularly difficult on a species with such a large home range.

All those highways and housing developments are putting a crimp in the mountain lions of the region’s gene pool, says a recent paper in PLoS ONE by University of California, Davis scientists. The mountain lions of the Santa Ana Mountains are no longer on speaking terms with the mountain lions of the Santa Monica Mountains. Within those population segments, genetic diversity is low.

I just covered this issue back in January (where the solution was a wildlife crossing) and wasn’t sure it was worth writing about again, but a the UC Davis press release and a Los Angeles Times article pointed out that we’ve seen this phenomenon of mountain lions hemmed in by a growing human population before — in the Florida panther. Other Puma populations may not be as distinctive as the Florida panther, but we are almost certainly sure to see this again. If there is a solution, it is a story worth following.

Read the PLoS ONE paper here.

Read the UC Davis press release here.

Read the Los Angeles Times story here.

Photo/map: This map identifies puma captures in the Santa Ana Mountains and eastern Peninsular ranges of southern California. The inset photo is of a mountain lion keeping watch while her juvenile cubs feed. Courtesy: UC Davis/The Nature Conservancy

Why migrating, tree-roosting bats are more susceptible to being killed by wind turbines has been a mystery. In a recent issue of the

Why migrating, tree-roosting bats are more susceptible to being killed by wind turbines has been a mystery. In a recent issue of the  A new report from WWF

A new report from WWF