Nashville Public Radio reports that two timber rattlesnakes with heads deformed from a fungus have been found in Tennessee. It’s unclear who the wildlife biologists who are reporting the fungus are (state? university?), but the story quotes Ed Carter, head of the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency and TWRA biologist Brian Flock.

Nashville Public Radio reports that two timber rattlesnakes with heads deformed from a fungus have been found in Tennessee. It’s unclear who the wildlife biologists who are reporting the fungus are (state? university?), but the story quotes Ed Carter, head of the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency and TWRA biologist Brian Flock.

Read the Nashville Public Radio story here.

A condensed version of the story was distributed by the Associated Press. Read it on the WBIR website, here.

The rattlesnake fungus has devastated the rattlesnake population in neighboring New Hampshire, so the Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife isn’t waiting around to find out what’s going on with its own rattlesnakes, which are only found in one area in the western part of the state.

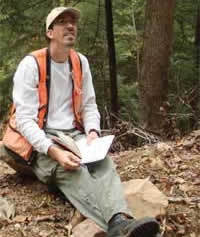

Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department rattlesnake project leader Doug Blodgett says in a department press release that lesions have been found in rattlesnakes last year and in several other species of snakes in the state.

Read the Vermont Fish and Wildlife press release here.

Photo: Vermont Fish & Wildlife biologist Doug Blodgett carefully examines a timber rattlesnake icheck it for signs of snake fungal disease. Photo by Tom Rogers, Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department.

The

The