White nose syndrome was discovered in the Russell Cave complex in Jackson County, Alabama on March 1 by a team of surveyors from Alabama A&M University and the National Park Service and has just been confirmed by Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study unit at the University of Georgia, according to an Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources press release.

White nose syndrome was discovered in the Russell Cave complex in Jackson County, Alabama on March 1 by a team of surveyors from Alabama A&M University and the National Park Service and has just been confirmed by Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study unit at the University of Georgia, according to an Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources press release.

The finding was both disappointing and a bit of a surprise because scientists had thought that the South’s shorter winters would curtail the spread of the cold-loving fungus.

According to the Washington Post, no bats were found dead of white nose syndrome in the cave. This suggests a situation similar to the suspected case in Oklahoma (which was not confirmed), where white nose syndrome was found, but did not kill bats.

Alabama has many caves and is home to millions of bats, including the federally endangered gray bat.

The Washington Post article says: “[Alabama] State wildlife biologist Keith Hudson called Alabama the Grand Central Station for the endangered gray bat.”

Read the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources press release here.

Read the Washington Post article here.

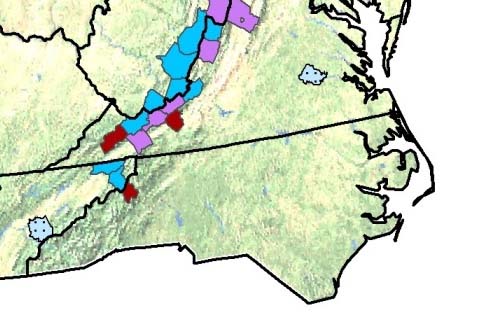

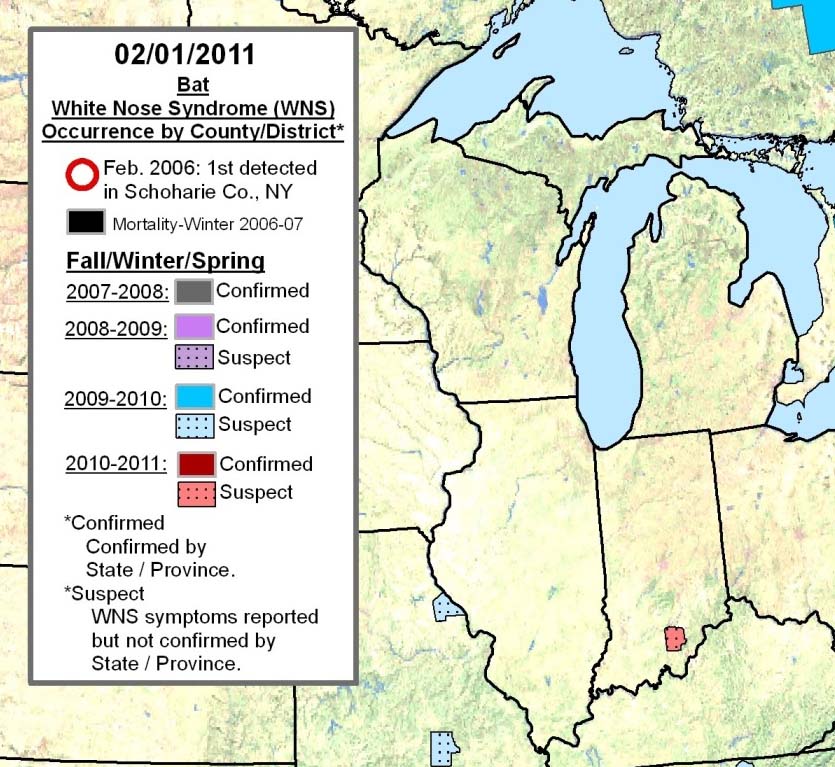

Map: Showing the location of the white nose syndrome finding in Alabama. Map by Cal Butchkoski, PA Game Commission, courtesy of US Fish and Wildlife Service