An Alabama cave that contains contains the largest documented wintering colony of federally listed endangered gray bats — about a million of them — has been struck by white nose syndrome (WNS), the US Fish and Wildlife Service reported yesterday. The good news is that WNS is not known to cause death in gray bats.

An Alabama cave that contains contains the largest documented wintering colony of federally listed endangered gray bats — about a million of them — has been struck by white nose syndrome (WNS), the US Fish and Wildlife Service reported yesterday. The good news is that WNS is not known to cause death in gray bats.

The infected bats found in the cave were tri-colored bats (aka eastern pipestrelles).

“With over a million hibernating gray bats, Fern Cave is undoubtedly the single most significant hibernaculum for the species,” said Paul McKenzie, Endangered Species Coordinator for the Service in the press release. “Although mass mortality of gray bats has not yet been confirmed from any WNS infected caves in which the species hibernates, the documentation of the disease from Fern Cave is extremely alarming and could be catastrophic. The discovery of WNS on a national wildlife refuge only highlights the continued need for coordination and collaboration with partners in addressing this devastating disease.”

Read the entire release, which has lots of details about the cave and how the infection was found, here.

In Canada, Environment Canada has committed to an additional $330,000 over four years for national coordination, surveillance and response to WNS. The US has had a national WNS coordinator (Jeremy Coleman, USFWS) for five years. The Canadian funds will go to the Canadian Cooperative Wildlife Health Centre.

“Canadian biologists and managers have done an incredible job responding to the threat of this disease with the resources they have,” said Katie Gillies, Imperiled Species Coordinator at Bat Conservation International in a letter to that organization’s members. “But hiring a formal WNS coordinator will certainly streamline those efforts and maximize their impact on this tragic disease. This is a very important step.

Read the Environment Canada press release here and here.

Photo: Gray bats, courtesy USFWS

Black bears are back in northeastern Alabama and southern New Jersey, recent reports say.

Black bears are back in northeastern Alabama and southern New Jersey, recent reports say. Oregon vesper sparrow and Mazama pocket gopher; mountain plover, burrowing owl and McCown’s longspur; the palila, a rapidly-declining Hawaiian honeycreeper; Karner blue butterfly, grasshopper sparrow, Henslow’s sparrow, and northern harrier; and white-tailed, Gunnison’s, Utah, and black-tailed prairie dogs are among the non-game species to benefit from this round of the

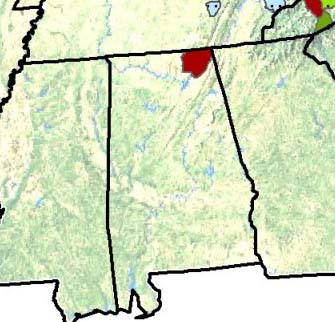

Oregon vesper sparrow and Mazama pocket gopher; mountain plover, burrowing owl and McCown’s longspur; the palila, a rapidly-declining Hawaiian honeycreeper; Karner blue butterfly, grasshopper sparrow, Henslow’s sparrow, and northern harrier; and white-tailed, Gunnison’s, Utah, and black-tailed prairie dogs are among the non-game species to benefit from this round of the  White nose syndrome was discovered in the Russell Cave complex in Jackson County, Alabama on March 1 by a team of surveyors from Alabama A&M University and the National Park Service and has just been confirmed by Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study unit at the University of Georgia, according to

White nose syndrome was discovered in the Russell Cave complex in Jackson County, Alabama on March 1 by a team of surveyors from Alabama A&M University and the National Park Service and has just been confirmed by Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study unit at the University of Georgia, according to