<!–[if !mso]> st1:*{behavior:url(#ieooui) } <![endif]–>

st1:*{behavior:url(#ieooui) } <![endif]–>

|

| Black duck |

<!–[if !mso]> st1:*{behavior:url(#ieooui) } <![endif]–>

st1:*{behavior:url(#ieooui) } <![endif]–>

|

| Black duck |

The State of Alaska has made it illegal for the public to use a Taser on wildlife. The stated fear is “catch and release” hunting — that someone would stun a moose or a bear long enough for a photo op, then release the animal, an article in the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner reports.

|

|

| The Taser X3W |

You might think that the inevitable injury to the “hunter” would nip this practice faster than any law would, but with yet another Jackass movie coming out in a few months, what more proof do you need that some people never learn?

The Alaska law seems wiser with the knowledge that Taser International recently introduced the Taser X3W Wildlife Electronic Control Device, a stun gun specifically designed for wildlife management. (The company’s press release for the product is here.)

It can, and has been, used to haze bears, but it can also be used in place of tranquilizer darts under certain conditions. One suggested use is to stun an animal so that a tranquilizer can be injected more accurately. Another use is to stun the animal briefly (15 seconds is one time I saw), for quick actions like taking a chicken feeder off a moose’s head. (As mentioned in the newspaper article.)

The magazine Wildlife Professional has a review of the use of stun guns on wildlife in its current issue. You can read it here. That article contains a link to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game’s operating procedures for stun guns.

Photo: TASER International

|

| Multiflora rose |

Think before you raze a stand of autumn olive, multiflora rose, or buckthorn, urged John Litvatis of the University of New Hampshire at a well-attended session at the Northeast Fish and Wildlife Conference this week.

For over a decade, most wildlife management agencies have had a policy of removing invasive species whenever they are found. Sometimes, though, the removal can do more harm than good. For example, the prickly tangle created by a stand of multiflora rose provides good habitat for the imperiled New England cottontail. Take away the rose bushes, and the cottontails might be quickly gobbled by predators.

If there was nothing but multiflora rose as far as the eye could see, though, then that monoculture would almost certainly need to be restored to some sort of balance, Litvatis said. But in many cases the aggressive — and reflexive — suppression of invasive shrubs may not be necessary.

Litvatis knew he was suggesting something against accepted wisdom, so he repeated that he was not advocating planting invasive species, just a more thoughtful approach to their removal, including the idea that sometimes it is best to leave things alone.

Litvatis flashed a slide with the names of other biologists in the Northeast who are with him in urging a more thoughtful approach to the management of invasive species. The audience stayed well into the break after the session, and not a single commenter attacked the idea or dismissed it out of hand. Food for thought.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons. JoJan

Getting permission from hundreds of private landowners for scat studies or trapping can make surveying coyote populations in the East tough. Sara Hansen, a grad student at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, tested a method using coyote vocalizations, and found it was effective.

Getting permission from hundreds of private landowners for scat studies or trapping can make surveying coyote populations in the East tough. Sara Hansen, a grad student at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, tested a method using coyote vocalizations, and found it was effective.

Her method was to play a recording of a coyote vocalization while observers listened from three points along a road. When a coyote responded, the observers took a compass bearing for the spot. The project had 541 survey points and got 117 responses.

To play the vocalization, two megaphones, two mini-amps and an mp3 player with a 20 second recording of coyote vocalization from the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology collection were used. Hansen says the set up cost about $60.

Hansen was able to test the method’s effectiveness because another project at the school had radio-collared coyotes. Estimating total population from the responses requires an algorithm, but Hansen found that triangulating the compass bearings from the observers who heard the howl worked very well.

She found that wind speeds were important, and that the method was not effective when wind speeds were over 5 km/hour. Running water was also a problem, and hemlocks, she said, “were kryptonite.”

Hansen gave her presentation at the Northeast Fish and Wildlife Conference yesterday. Unfortunately, there doesn’t seem to be a published paper for more details, but this five-page grant report does have some details. Also, this progress report has some info. (It is a PDF and the information on this project starts at the bottom of page 9.)

By the way, she estimates New York’s coyote population to be 30,000 to 35,000.

White nose syndrome has been found in Nova Scotia, the fourth Canadian province to be stricken with the bat disease. The syndrome was detected in a bat found flying in daylight on March 23 in the town of Brooklyn, in Hant County. White nose syndrome had been previously found in Canada in Ontario, Quebec, and New Brunswick.

White nose syndrome has been found in Nova Scotia, the fourth Canadian province to be stricken with the bat disease. The syndrome was detected in a bat found flying in daylight on March 23 in the town of Brooklyn, in Hant County. White nose syndrome had been previously found in Canada in Ontario, Quebec, and New Brunswick.

Alison Whitlock, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Northeast white nose syndrome coordinator mentioned the news during her presentation on the white nose syndrome national plan at the Northeast Fish & Wildlife Conference yesterday.

Find out more from the Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources press release here. News stories appeared in The Global Saskatoon, The Canadian Press, and Halifax News Net.

White nose syndrome has been found in Nova Scotia, the fourth Canadian province to be stricken with the bat disease. The syndrome was detected in a bat found flying in daylight on March 23 in the town of Brooklyn, in Hant County. White nose syndrome had been previously found in Canada in Ontario, Quebec, and New Brunswick.

White nose syndrome has been found in Nova Scotia, the fourth Canadian province to be stricken with the bat disease. The syndrome was detected in a bat found flying in daylight on March 23 in the town of Brooklyn, in Hant County. White nose syndrome had been previously found in Canada in Ontario, Quebec, and New Brunswick.

Alison Whitlock, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Northeast white nose syndrome coordinator mentioned the news during her presentation on the white nose syndrome national plan at the Northeast Fish & Wildlife Conference yesterday.

Find out more from the Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources press release here. News stories appeared in The Global Saskatoon, The Canadian Press, and Halifax News Net.

Make sure you get all the latest news and information from State Wildlife Research News. Subscribe now, by sending an email to wildliferesearchnews@gmail.com. Each week you’ll receive the top stories in your email box. Just click on the stories that interest you for more information. It’s the best way to keep on top of the latest wildlife research news.

A second generation of more potent anticoagulant rodenticides (aka, rat poisons) are prevalent in raptors brought to the Tufts Veterinary School wildlife health clinic in Massachusetts, said Maureen Murray of Tufts at a session at the Northeast Fish and Wildlife Conference today.

She tested 161 raptors that were brought in dead or died at the clinic for residues of the second generation of rat poisons, which kill by causing the animal to bleed to death. She found that 86 percent of them had residues of the poison in their systems. She also found that amount of rat poison that was fatal to the raptors varied greatly between individuals. For example, on bird appeared to have died with 12 parts per billion (ppb) of the poison in its blood. Another had clearly died of other causes, even though it had 260 ppb.

Murray noted that the EPA has banned the sale of these second generation of poisons to the public, as of June. She suspects the incidence of the poisons in the environment will not decline significantly however, since they will still be available to pest control professionals.

Murray says that poisoning with these anticoagulant rodenticides should be considered when pondering unexplained raptor die-offs.

|

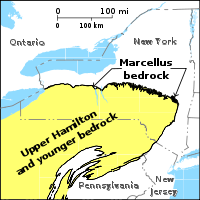

| Map by Dhaluza |

Got shale? Marcellus Shale, that is. Fish and Wildlife agencies in the region should start taking baseline readings now, before gas extraction infrastructure is even in place, advised the US Fish and Wildlife Service at a session at the 67th annual Northeast Fish & Wildlife Conference taking place this week in Manchester, NH.

Extractions from the Marcellus Shale are one of the emerging environmental contaminants the service feels wildlife managers should be aware of. outlined in a session at the conference by Margaret Byrne and Meagan Racey. Other emerging issues include nanomaterials, particularly the impact of nanosilver, an antimicrobial material found in consumer products that is already being discharged into waterways through sewer systems, and the impact of climate change on contanimants already in the environment. For example, at higher termpratures mercury forms methyl mercury, a more potent form of the toxic metal.

|

| Giant salvinia in Caddo Lake |

The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department reports that last year’s campaign to increase the public’s awareness of the invasive aquatic plant giant salvinia reached more than half of its intended audience. Of the boaters living within 60 miles of four lakes in east Texas who saw an ad or information about giant salvinia, 96 percent said they were “more likely to clean their boat, trailer or gear….”

Giant salvinia (Salvinia molesta) is a native of Brazil that came to North America as a plant for water gardens. It can grow up to three feet thick, and can double in size in a week. It has plagued the lakes of eastern Texas for over 10 years, and is also found in Alabama, Arizona, California, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, and South Carolina.

According to a department release, the campaign included floating messages on buoys near key boat ramps, fish measuring rulers with campaign messages, online web banner ads, Twitter and Facebook posts, gasoline-pump toppers, billboard ads near key lakes, and a cute television public service announcement (PSA) that personifies giant salvinia as a doofus hoping to hitch a ride with a boater to cause trouble in other lakes.

The campaign was so successful that the department may try a similar effort for zebra mussels, which are not yet as established in the state as giant salvinia.

Read the full press release here. You can find the press releases, radio spots, a PDF of the ruler, and two versions of the television PSA here.

Photo: Giant salvinia in Caddo Lake, Texas, © Texas Parks and Wildlife Department