Carroll Henderson, who has been supervisor of the Nongame Wildlife Program at the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR) since 1977, was awarded the North American Bird Conservation Initiative (NABCI) Gary T. Myers Bird Conservation Award at the North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference in Atlanta, Georgia last week.

A US Fish and Wildlife Service press release says that the award recognized Henderson for, “successful bird conservation initiatives involving research, endangered species protection and restoration, habitat preservation, collaboration with state and federal wildlife agencies, promotion of nature tourism, and educational efforts including more than 1,000 public presentations.”

Henderson has also written 11 books and has lead 49 international bird watching tours.

Read the Minnesota DNR press release announcing the award, here.

To learn more about Henderson, and his experiences as a nongame program supervisor, read a Q&A with him on the Minnesota Trails website.

“If you act appropriately and you carry bear spray, you are much better off than just blundering into bear country with a large firearm,” said Brigham Young University researcher Tom Smith

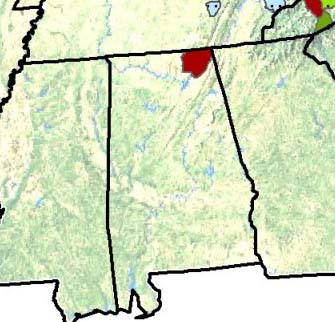

“If you act appropriately and you carry bear spray, you are much better off than just blundering into bear country with a large firearm,” said Brigham Young University researcher Tom Smith  White nose syndrome was discovered in the Russell Cave complex in Jackson County, Alabama on March 1 by a team of surveyors from Alabama A&M University and the National Park Service and has just been confirmed by Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study unit at the University of Georgia, according to

White nose syndrome was discovered in the Russell Cave complex in Jackson County, Alabama on March 1 by a team of surveyors from Alabama A&M University and the National Park Service and has just been confirmed by Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study unit at the University of Georgia, according to  On the last day of the comment period, a group of

On the last day of the comment period, a group of  Four years ago a science journal article was published saying that most of the bats found dead at an Alberta wind farm had no signs of external injuries, but their lungs were damaged. The verdict: barotrauma, damage caused by a sharp change in pressure. In humans the most common example is when you rupture an ear drum while on an airplane.

Four years ago a science journal article was published saying that most of the bats found dead at an Alberta wind farm had no signs of external injuries, but their lungs were damaged. The verdict: barotrauma, damage caused by a sharp change in pressure. In humans the most common example is when you rupture an ear drum while on an airplane.

Usually it is hard enough figuring out what’s stressing species right now to figure out which may need protection. Predicting the future — such as how land uses might change — adds another level of complexity. Figuring out the impact of climate change, with its assortment of predictive models, is more complex still.

Usually it is hard enough figuring out what’s stressing species right now to figure out which may need protection. Predicting the future — such as how land uses might change — adds another level of complexity. Figuring out the impact of climate change, with its assortment of predictive models, is more complex still.