Winter tick infestations in moose can become so severe that the moose rub the hair right off their bodies. These have been called “ghost moose,” because of the whiteness of the mooses’ bare bodies. The tick infestation can lead to death from: anemia, distraction from grazing, or exposure to cold.

Estimating winter tick populations is an important component of moose management.

Research in New Hampshire found that counting winter ticks by any of three different methods turned up similar results. Winter tick populations were monitored by:

-dragging a white sheet over low vegetation in the spring,

-counting ticks on hunter-killed moose at check-in stations in the fall, and

-noting hair loss patterns on moose in the spring.

The three methods all revealed a similar pattern of lower winter tick numbers in 2008 and 2009, with a spike in 2010.

You can read about the New Hampshire research in an article written for a general audience in New Hampshire Fish & Game’s magazine, Wildlife Journal.

Alces Journal published a paper that reached a similar conclusion. The research there was in Maine, however. Read the paper here.

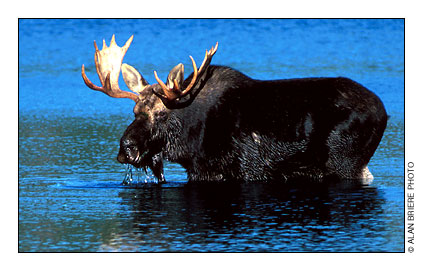

Photo: Alan Briere, courtesy NH Fish & Game