Dams — some built over 200 years ago — cut off Atlantic salmon from their spawning grounds from central Maine to Connecticut. An attempt to bring back the Connecticut River’s salmon has not been successful, but in Maine, on the Kennebec River, salmon surged back when dams were removed.

On the Penobscot River, also in central Maine, a few Atlantic salmon had always returned to the river, but dams blocked the way to most of their spawning grounds, in spite of a fish elevator that helped them past the first dam.

When first two dams on the river are removed, the way will be clear for the salmon to get to most of their historic spawning streams in New England’s second-largest watershed. Here’s a Nature Conservancy Magazine article detailing the situation three years ago.

Here’s an Associated Press story about the removal of the dam, scheduled for Monday, July 22.

And here’s a story from the Lewiston Sun Journal.

The US Fish and Wildlife Service’s northeastern section blog covered it here and here.

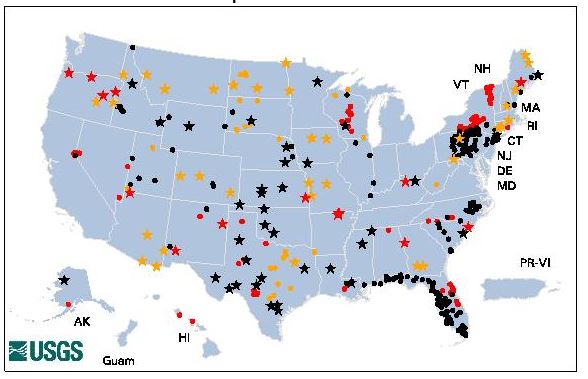

One way for the federal government to save money is to turn off any number of the 7,000 river gauges installed and maintained by the US Geological Survey. Each gauge costs $14,000 to $18,000 a year to maintain,

One way for the federal government to save money is to turn off any number of the 7,000 river gauges installed and maintained by the US Geological Survey. Each gauge costs $14,000 to $18,000 a year to maintain,  The news is not that

The news is not that When wolves were restored to Yellowstone National Park, its riparian habitats bounced back. But it takes more than wolves killing elk to restore these habitats, a recent paper in the

When wolves were restored to Yellowstone National Park, its riparian habitats bounced back. But it takes more than wolves killing elk to restore these habitats, a recent paper in the  If you work with freshwater mussels, you know that their larval form, known as glochidia, often must live as a parasite in a suitable species of fish to survive. Georgia Department of Natural Resources (DNR) and University of Georgia scientists have discovered that that relationship may work the other way as well: in 2009 DNR zoologist Jason Wisniewski found a developing shad egg inside the shell of a freshwater mussels.

If you work with freshwater mussels, you know that their larval form, known as glochidia, often must live as a parasite in a suitable species of fish to survive. Georgia Department of Natural Resources (DNR) and University of Georgia scientists have discovered that that relationship may work the other way as well: in 2009 DNR zoologist Jason Wisniewski found a developing shad egg inside the shell of a freshwater mussels.