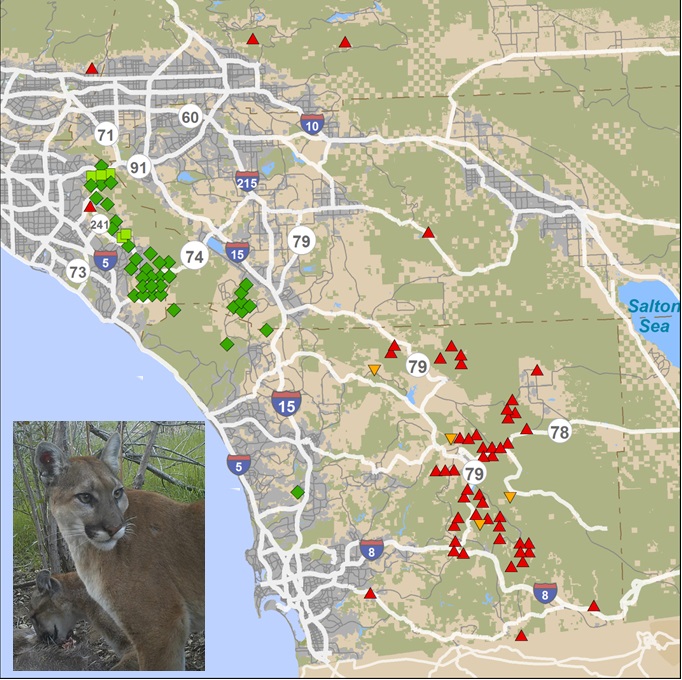

The mountain lions of southern California are hemmed in on all sides. In one place a 10-lane highway divides mountain lion habitat. All that development is particularly difficult on a species with such a large home range.

The mountain lions of southern California are hemmed in on all sides. In one place a 10-lane highway divides mountain lion habitat. All that development is particularly difficult on a species with such a large home range.

All those highways and housing developments are putting a crimp in the mountain lions of the region’s gene pool, says a recent paper in PLoS ONE by University of California, Davis scientists. The mountain lions of the Santa Ana Mountains are no longer on speaking terms with the mountain lions of the Santa Monica Mountains. Within those population segments, genetic diversity is low.

I just covered this issue back in January (where the solution was a wildlife crossing) and wasn’t sure it was worth writing about again, but a the UC Davis press release and a Los Angeles Times article pointed out that we’ve seen this phenomenon of mountain lions hemmed in by a growing human population before — in the Florida panther. Other Puma populations may not be as distinctive as the Florida panther, but we are almost certainly sure to see this again. If there is a solution, it is a story worth following.

Read the PLoS ONE paper here.

Read the UC Davis press release here.

Read the Los Angeles Times story here.

Photo/map: This map identifies puma captures in the Santa Ana Mountains and eastern Peninsular ranges of southern California. The inset photo is of a mountain lion keeping watch while her juvenile cubs feed. Courtesy: UC Davis/The Nature Conservancy

Why migrating, tree-roosting bats are more susceptible to being killed by wind turbines has been a mystery. In a recent issue of the

Why migrating, tree-roosting bats are more susceptible to being killed by wind turbines has been a mystery. In a recent issue of the  A new report from WWF

A new report from WWF “What we did to protect animals actually protected roads,” said Vermont Agency of Natural Resources secretary Deb Markowitz at a general session at the Northeastern Transportation and Wildlife Conference this week (Sept. 21 – 24) in Burlington, Vermont. In places where culverts had been resized to allow wildlife to walk along the banks during low flow periods, the culverts have held during floods like the one caused by Tropical Storm Irene in Vermont.

“What we did to protect animals actually protected roads,” said Vermont Agency of Natural Resources secretary Deb Markowitz at a general session at the Northeastern Transportation and Wildlife Conference this week (Sept. 21 – 24) in Burlington, Vermont. In places where culverts had been resized to allow wildlife to walk along the banks during low flow periods, the culverts have held during floods like the one caused by Tropical Storm Irene in Vermont. Black racer snakes are rare in Vermont, so when highway construction was going to introduce drains with holes big enough for the snakes to fall into, the Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife asked for a fix. Drain covers with smaller holes were not possible. So the Vermont Agency of Transportation fashioned snake-sized ladders and attached them to the drains. It turns out that black racers are excellent climbers, so it is expected that the snakes will rescue themselves if they fall into the drain. A poster on the unusual solution was presented at the Northeastern Transportation and Wildlife Conference, being held this week (Sept. 21 – 24) in Burlington, Vermont.

Black racer snakes are rare in Vermont, so when highway construction was going to introduce drains with holes big enough for the snakes to fall into, the Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife asked for a fix. Drain covers with smaller holes were not possible. So the Vermont Agency of Transportation fashioned snake-sized ladders and attached them to the drains. It turns out that black racers are excellent climbers, so it is expected that the snakes will rescue themselves if they fall into the drain. A poster on the unusual solution was presented at the Northeastern Transportation and Wildlife Conference, being held this week (Sept. 21 – 24) in Burlington, Vermont.

Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease (EHD) has been confirmed as the cause of death in over 100 deer in southwestern Oregon,

Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease (EHD) has been confirmed as the cause of death in over 100 deer in southwestern Oregon,  People love birds, and that makes it relatively easy to mobilize citizen scientists for bird research. Recently, the International Rusty Blackbird Working Group did just that to learn more about the spring migration of a bird that is in a mysterious decline. The insights are still to come, but the data collection has been deemed a success.

People love birds, and that makes it relatively easy to mobilize citizen scientists for bird research. Recently, the International Rusty Blackbird Working Group did just that to learn more about the spring migration of a bird that is in a mysterious decline. The insights are still to come, but the data collection has been deemed a success.