A tri-colored bat, found dead in Table Rock State Park in the northwestern corner of South Carolina, has been confirmed to have white nose syndrome (WNS), the Charlotte Observer and S.C. Department of Natural Resources report.

A tri-colored bat, found dead in Table Rock State Park in the northwestern corner of South Carolina, has been confirmed to have white nose syndrome (WNS), the Charlotte Observer and S.C. Department of Natural Resources report.

The SC DNR press release says:

The bat was collected on Feb. 21, transported on ice, and submitted to the Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study in Athens, Ga. The Wildlife Disease Study confirmed the presence of Geomyces destructans fungus, which causes WNS.

It further says:

“We have been expecting WNS in South Carolina,” said Mary Bunch, wildlife biologist with the S.C. Department of Natural Resources (DNR) based in Clemson. “We have watched the roll call of states and counties and Canadian provinces grow each year since the first bat deaths were noted in New York in 2007.”

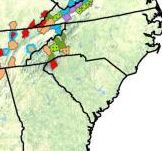

South Carolina is the 21st state to report a case of WNS. The roll cal includes five Canadian provinces. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s WNS map shows this newest WNS site as being located in the Appalachian Mountains, not far from many other Southern mountain sites in North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky and Virginia.

Read the Charlotte Observer article here.

Read the SC DNR press release here.

Illustration: The USFWS March 11, 2013 WNS map, showing a new site in Pickens County, South Carolina confirmed. Map by Carl Butchkoski, PA Game Commission

A study published recently in

A study published recently in Wisconsin researchers have confirmed that Geomyces destructans, the fungus that causes white nose syndrome (WNS) in bats, persists in caves long after all the bats in the cave have died off.

Wisconsin researchers have confirmed that Geomyces destructans, the fungus that causes white nose syndrome (WNS) in bats, persists in caves long after all the bats in the cave have died off. The Montana Natural Heritage Program is collecting baseline information on the state’s bats that will be vital if the state is ever struck with white nose syndrome (WNS),

The Montana Natural Heritage Program is collecting baseline information on the state’s bats that will be vital if the state is ever struck with white nose syndrome (WNS),