About a third of the ponds in a Missouri study harbored chytrid fungus. A Washington University in St. Louis scientist decided to take advantage of the fact that the fungus does not seem to cause amphibian deaths in the region, and tried to tease out the factors that lead to the fungus flourishing in one pond and not another.

About a third of the ponds in a Missouri study harbored chytrid fungus. A Washington University in St. Louis scientist decided to take advantage of the fact that the fungus does not seem to cause amphibian deaths in the region, and tried to tease out the factors that lead to the fungus flourishing in one pond and not another.

The 29 ponds studied were all roughly the same size and depth. They were clustered in the east-central section of Missouri (no surprise, around St. Louis).

No single factor determined which ponds had the fungus and which did not. But some fancy statistical analysis showed that the affected ponds shared amphibian community structure, macroinvertebrate community structure, and pond physicochemistry.

Since the research was done, crayfish and nematodes have been found to be infected with the chytrid fungus, making them possible reservoirs for the disease. This study suggested that variations in invertebrate communities was a factor in which ponds harbored the fungus.

In the paper, which was published in PLoS ONE, the researchers recommend that more research be done on the non-amphibian life in infected ponds to figure out how they are contributing to sustaining the fungus.

Read the Washington University in St. Louis article here.

Read the PLoS ONE paper here.

Photo: A pond survey crew samples the creatures that live in a Missouri pond in order to better understand the differences between ecosystems that favor chytrid and those that do not. Alex Strauss, the first author on this paper, is wearing a blue shirt. Photo credit: Elizabeth Biro/Washington University – Tyson Research Center

Antibiotic resistance isn’t just for humans and farm animals. An article in

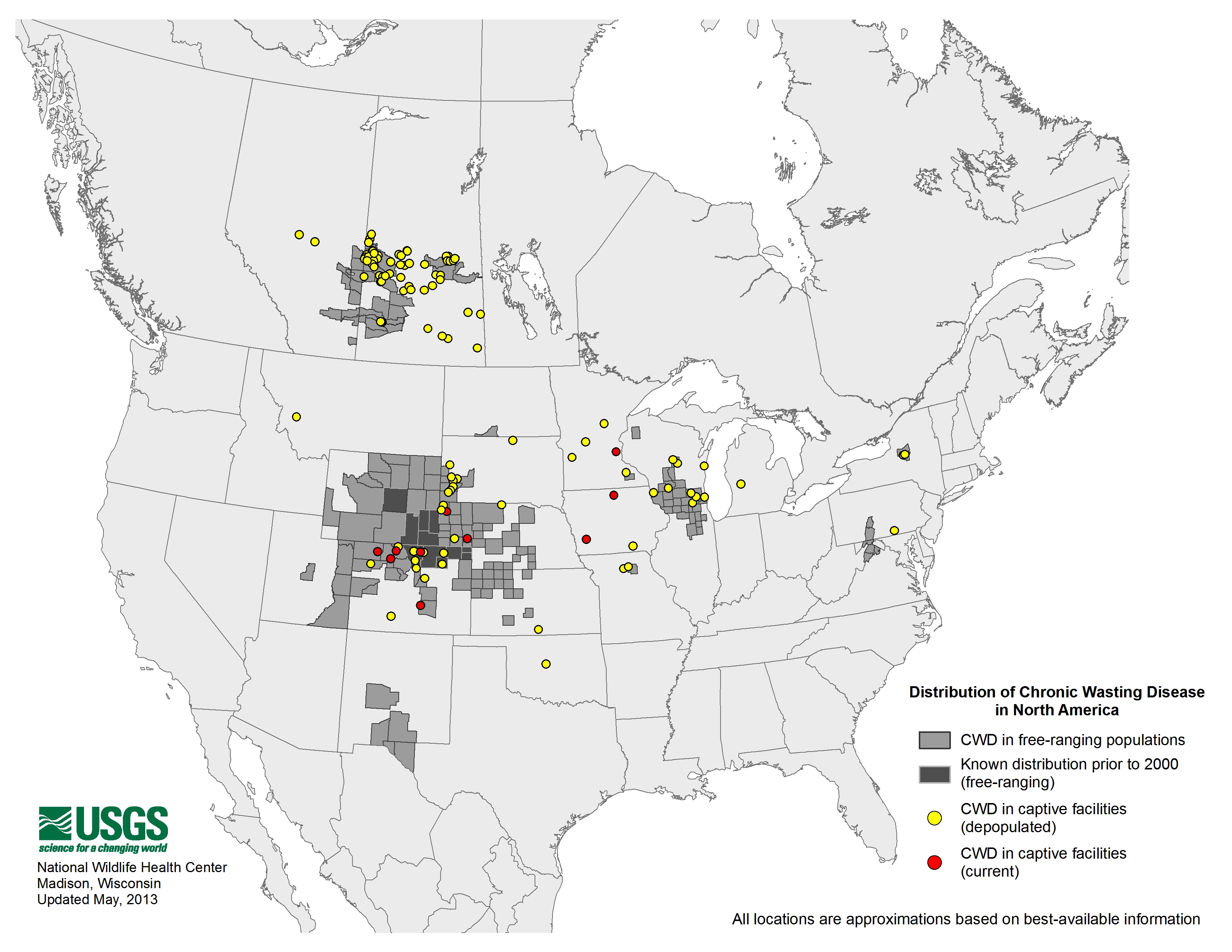

Antibiotic resistance isn’t just for humans and farm animals. An article in  Plants, including crop plants such as alfalfa and tomatoes, may serve as a reservoir for the prions, or misfolded proteins, that cause chronic wasting disease in deer (as well as other prion diseases such as scrapie in sheep, and mad cow disease), reports

Plants, including crop plants such as alfalfa and tomatoes, may serve as a reservoir for the prions, or misfolded proteins, that cause chronic wasting disease in deer (as well as other prion diseases such as scrapie in sheep, and mad cow disease), reports  About a third of the ponds in a Missouri study harbored chytrid fungus. A

About a third of the ponds in a Missouri study harbored chytrid fungus. A  A new species of chytrid fungus has a different ecological niche than the one that has been wiping out amphibians all over the globe, says John Platt it

A new species of chytrid fungus has a different ecological niche than the one that has been wiping out amphibians all over the globe, says John Platt it