The US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) announced yesterday that, for the first time, white nose syndrome has been documented in the endangered gray bat.

The US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) announced yesterday that, for the first time, white nose syndrome has been documented in the endangered gray bat.

The USFWS press release says:

“The documented spread of WNS on gray bats is devastating news. This species was well on the road to recovery, and confirmation of the disease is great cause for concern. Because gray bats hibernate together in colonies that number in the hundreds of thousands, WNS could expand exponentially across the range of the species,” said Paul McKenzie, Missouri Endangered Species Coordinator for the Service. “The confirmation of WNS in gray bats is also alarming because guano from the species is an important source of energy for many cave ecosystems and there are numerous cave-adapted species that could be adversely impacted by their loss.”

Also according to the release, the afflicted bats were found in Hawkins and Montgomery counties in Tennessee during two separate winter surveillance trips, conducted by the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency (TWRA) and The Nature Conservancy (TNC).

Read the USFWS press release here.

Photo: Photos of gray bats with white-nose syndrome from Hawkings and Montgomery counties, Tennessee, courtesy USFWS

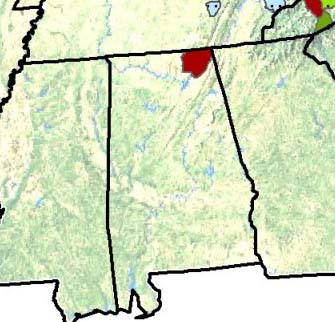

White nose syndrome was discovered in the Russell Cave complex in Jackson County, Alabama on March 1 by a team of surveyors from Alabama A&M University and the National Park Service and has just been confirmed by Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study unit at the University of Georgia, according to

White nose syndrome was discovered in the Russell Cave complex in Jackson County, Alabama on March 1 by a team of surveyors from Alabama A&M University and the National Park Service and has just been confirmed by Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study unit at the University of Georgia, according to  Four years ago a science journal article was published saying that most of the bats found dead at an Alberta wind farm had no signs of external injuries, but their lungs were damaged. The verdict: barotrauma, damage caused by a sharp change in pressure. In humans the most common example is when you rupture an ear drum while on an airplane.

Four years ago a science journal article was published saying that most of the bats found dead at an Alberta wind farm had no signs of external injuries, but their lungs were damaged. The verdict: barotrauma, damage caused by a sharp change in pressure. In humans the most common example is when you rupture an ear drum while on an airplane.