A recent study of sage grouse in northeastern Wyoming says that the population there is just one severe weather event or West Nile outbreak away from extirpation. The study was conducted by three University of Montana wildlife biologists on behalf of the US Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

A recent study of sage grouse in northeastern Wyoming says that the population there is just one severe weather event or West Nile outbreak away from extirpation. The study was conducted by three University of Montana wildlife biologists on behalf of the US Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

Read the report, a 46-page PDF, here.

Here’s the BLM web page with links to other info about the report

And here’s the story in the Casper Star-Tribune.

Despite the dire forecast, the Wyoming Game and Fish Commission will not close the three-day hunting season in northeastern Wyoming. The reasoning, says a Field & Stream blog post, is that because it is primarily energy development and disease, not hunting, that is causing the birds’ decline, hunters should not be penalized.

The blog post leans heavily on another article from the Casper Star-Tribune. Read that one here. That article notes that state biologists proposed closing the hunting season, but were over-ruled when dozens of people attended the Game and Fish Commission meeting to protest the closing. The article does not note the irony of the citizens who disagreed with the over-ruled scientists saying that the scientists’ recommendation was based on politics.

More troubling than even the possible extirpation of this population, or the politics behind the species’ management, is the fact that the Wyoming sage grouse management plan is the model for the nation. We’ve written about Wyoming’s plan being the national model before:

When a newspaper editorial praised the Wyoming sage grouse management plan;

And when the BLM took the lead on coordinating sage grouse management efforts across its range.

Photo: Greater sage grouse by Stephen Ting. Courtesy US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Factory-farmed bullfrogs carry the chytrid fungus, likely spreading the infection when they escape into the wild, says an

Factory-farmed bullfrogs carry the chytrid fungus, likely spreading the infection when they escape into the wild, says an

Things have actually been pretty quiet over the past month when it comes to wildlife diseases. The big news, of course, is

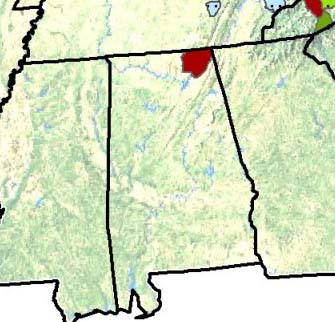

Things have actually been pretty quiet over the past month when it comes to wildlife diseases. The big news, of course, is  White nose syndrome was discovered in the Russell Cave complex in Jackson County, Alabama on March 1 by a team of surveyors from Alabama A&M University and the National Park Service and has just been confirmed by Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study unit at the University of Georgia, according to

White nose syndrome was discovered in the Russell Cave complex in Jackson County, Alabama on March 1 by a team of surveyors from Alabama A&M University and the National Park Service and has just been confirmed by Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study unit at the University of Georgia, according to