“Asian carp have harmed the ecosystem, the economy, property, and boaters in the Mississippi River system. The diet of Asian carp overlaps with the diet of native fishes in the Mississippi and Illinois Rivers, meaning the carp compete directly with native fish for food,” says the Asian Carp Regional Coordinating Committee website.

“Asian carp have harmed the ecosystem, the economy, property, and boaters in the Mississippi River system. The diet of Asian carp overlaps with the diet of native fishes in the Mississippi and Illinois Rivers, meaning the carp compete directly with native fish for food,” says the Asian Carp Regional Coordinating Committee website.

That website, and other information on Asian carp, emphasize the danger to humans from the carp. The carp are large and jump as high as 10 feet out of the water when startled. Since passing boats startle the fish, they injure boaters.

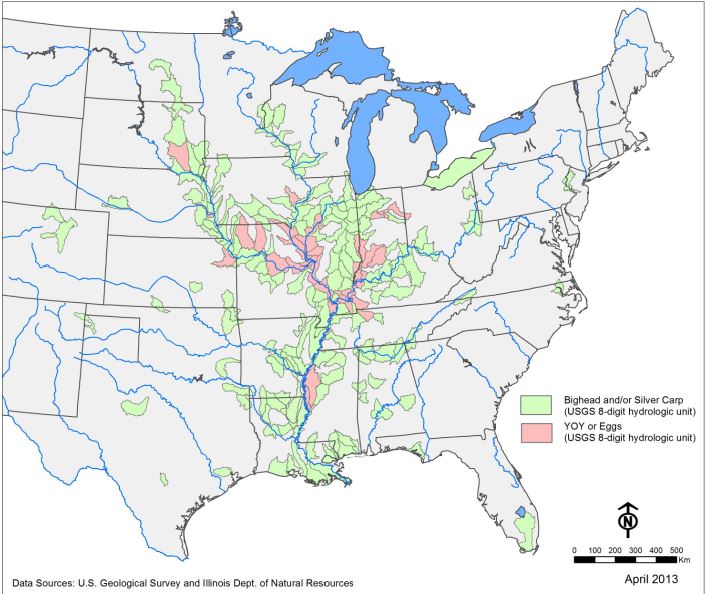

The focus has been on keeping Asian carp, a term that includes both bighead carp and silver carp out of the Great Lakes, which already has enough invasive species, thank you, and where the carp are expected to do horrible things to the food chain.

This week, however, the bad news is that Asian carp have spread farther north in the Mississippi River. Their eggs have been found as far north as Lynxville, Wisc.

“This discovery means that Asian carp spawned much farther north in the Mississippi than previously recorded,” said Leon Carl, US Geological Survey Midwest Regional Director in a USGS press release. “The presence of eggs in the samples indicates that spawning occurred, but we do not know if eggs hatched and survived or whether future spawning events would result in live fish.”

Read the USGS press release with all the details, here.

Read an article in the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, based mostly on the press release here.

Another article, in the Minneapolis Star-Tribune, also leans heavily on the press release. Read it here.

Map: Asian carp distribution, as of April 2013. Map courtesy of Asian Carp Regional Coordinating Committee

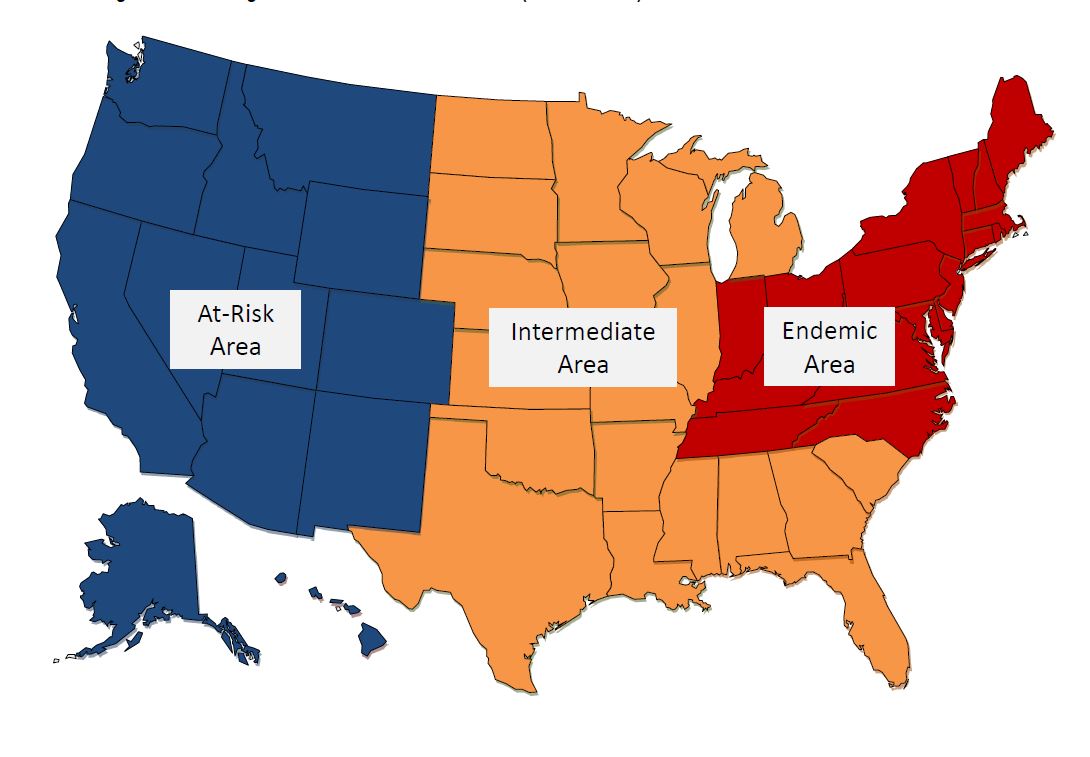

Sorry for the double dose of white nose syndrome (WNS) news, but I didn’t want this to get lost in yesterday’s post on the the new WNS protocol, even though it was included in the same

Sorry for the double dose of white nose syndrome (WNS) news, but I didn’t want this to get lost in yesterday’s post on the the new WNS protocol, even though it was included in the same  The National Wildlife Health Center (in Madison, Wisc., part of the US Geological Survey) has updated the Bat Submission Guidelines for the 2013/2014 white nose syndrome (WNS) surveillance season.These are the protocols that you, a state wildlife biologist, would use to submit a bat or other sample to the center for WNS diagnosis.

The National Wildlife Health Center (in Madison, Wisc., part of the US Geological Survey) has updated the Bat Submission Guidelines for the 2013/2014 white nose syndrome (WNS) surveillance season.These are the protocols that you, a state wildlife biologist, would use to submit a bat or other sample to the center for WNS diagnosis. One way for the federal government to save money is to turn off any number of the 7,000 river gauges installed and maintained by the US Geological Survey. Each gauge costs $14,000 to $18,000 a year to maintain,

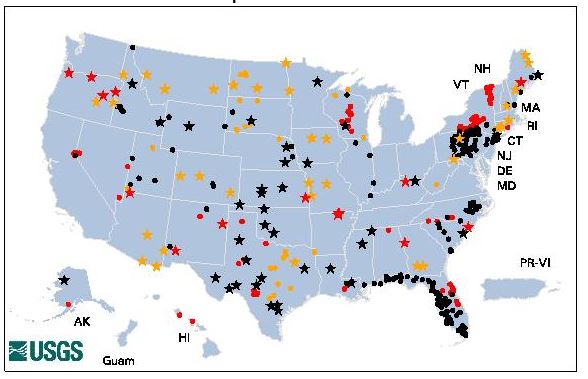

One way for the federal government to save money is to turn off any number of the 7,000 river gauges installed and maintained by the US Geological Survey. Each gauge costs $14,000 to $18,000 a year to maintain,  Today is the second day in a US Geological Survey amphibian two-fer. If you like your wildlife moist and federally researched, you’ve come to the right place.

Today is the second day in a US Geological Survey amphibian two-fer. If you like your wildlife moist and federally researched, you’ve come to the right place. There have been studies that have calculated the likelihood of extinction for various amphibian species, but the first study to calculate how fast amphibian populations are declining was recently published in

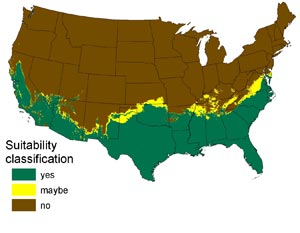

There have been studies that have calculated the likelihood of extinction for various amphibian species, but the first study to calculate how fast amphibian populations are declining was recently published in  In 2008 the US Geological Survey published a report that said that the entire southern third of the United States could provide habitat for the invasive Burmese python that has been roiling the Florida Everglades ecoystem.

In 2008 the US Geological Survey published a report that said that the entire southern third of the United States could provide habitat for the invasive Burmese python that has been roiling the Florida Everglades ecoystem. On an August day 17 years ago, eight Minnesota junior high school students on a field trip caught 22 frogs in a farm pond. At least half of the frogs had some abnormality, mostly in their hind legs. The conscientious teacher reported the group’s finding to the state. Dutiful state scientists surveyed wetlands across Minnesota and found at least one hotspot of frog abnormality in every county in the state.

On an August day 17 years ago, eight Minnesota junior high school students on a field trip caught 22 frogs in a farm pond. At least half of the frogs had some abnormality, mostly in their hind legs. The conscientious teacher reported the group’s finding to the state. Dutiful state scientists surveyed wetlands across Minnesota and found at least one hotspot of frog abnormality in every county in the state. Where did the turtle cross the road? A citizen scientist has the answer, particularly in Massachusetts, where over the last few years citizen scientists have been tracking turtle crossings as part of the Turtle Roadway Mortality Monitoring Program. Volunteers are trained by Linking Landscapes for Massachusetts Wildlife, a partnership between Division of Fisheries and Wildlife (DFW), Department of Transportation (DOT) Highway Division and the University of Massachusetts-Amherst.

Where did the turtle cross the road? A citizen scientist has the answer, particularly in Massachusetts, where over the last few years citizen scientists have been tracking turtle crossings as part of the Turtle Roadway Mortality Monitoring Program. Volunteers are trained by Linking Landscapes for Massachusetts Wildlife, a partnership between Division of Fisheries and Wildlife (DFW), Department of Transportation (DOT) Highway Division and the University of Massachusetts-Amherst.