Why migrating, tree-roosting bats are more susceptible to being killed by wind turbines has been a mystery. In a recent issue of the Proceedings of the National Academies of Science (PNAS), US Geological Survey scientist Paul Cryan offers an explanation: under certain wind conditions, the air currents around turbines is similar enough to the air currents around trees to confuse the bats into thinking the turbines are big trees.

Why migrating, tree-roosting bats are more susceptible to being killed by wind turbines has been a mystery. In a recent issue of the Proceedings of the National Academies of Science (PNAS), US Geological Survey scientist Paul Cryan offers an explanation: under certain wind conditions, the air currents around turbines is similar enough to the air currents around trees to confuse the bats into thinking the turbines are big trees.

The paper says that the bats congregate on the downwind side of trees to feast on the flying insects that congregate there. The paper doesn’t make this comparison, but it’s a lot like trout hanging out in an eddy, waiting for insects and other edibles to join them.

The problem, of course, is that spinning blades and barotrauma are not kind to bats that hang around wind turbines.

Two of the take-aways from the paper are that turbine operators can put bat deterrents on the downwind side of the turbines, and that changing the operating parameters of the turbines could help save bats, such as preventing the blades from turning in a sudden gust on an otherwise calm night.

Read the PNAS paper, here.

Read a Washington Post paper on the study and the white nose syndrome threat, here. (But note that it never mentions that one group of bat speices is more vulnerable to white nose syndrome, while a different group of bats is more vulnerable to wind turbines.)

A summary of the paper in the Discover Magazine blog is here.

A different summary of the paper in the Popular Science blog is here.

And just for good luck, here is the write-up from Conservation Magazine.

Photo: Instead of going with a generic bat photo, since I don’t seem to have any of common migrating bats, I went with a generic wind farm photo. This is not the wind farm that was studied in the Cryan paper. Lovely photo by by Joshua Winchell.

As the second state struck by white nose syndrome in bats, good news for Vermont’s bats is good news for all hibernating bats in North America. An Associated Press story reports that scientists are interpreting results of a winter-long study of bat movements in New England’s largest bat hibernation site as showing a sharp reduction in the number of bats felled by white nose syndrome.

As the second state struck by white nose syndrome in bats, good news for Vermont’s bats is good news for all hibernating bats in North America. An Associated Press story reports that scientists are interpreting results of a winter-long study of bat movements in New England’s largest bat hibernation site as showing a sharp reduction in the number of bats felled by white nose syndrome. A paper in the recent issue of

A paper in the recent issue of  After the Wallow Fire, Arizona’s largest wildfire, burned 538,000 acres, a half-dozen biologists lead by Northern Arizona University researchers came in to study bats’ reaction to the changed ecosystem, an article in

After the Wallow Fire, Arizona’s largest wildfire, burned 538,000 acres, a half-dozen biologists lead by Northern Arizona University researchers came in to study bats’ reaction to the changed ecosystem, an article in  From a

From a  After detecting the fungus that causes white nose syndrome, but not seeing any bats with the disease, for two winters in a row, dead bats showing the symptoms caused by the white nose syndrome fungus were found in an Arkansas cave on January 11, an

After detecting the fungus that causes white nose syndrome, but not seeing any bats with the disease, for two winters in a row, dead bats showing the symptoms caused by the white nose syndrome fungus were found in an Arkansas cave on January 11, an Sorry for the double dose of white nose syndrome (WNS) news, but I didn’t want this to get lost in yesterday’s post on the the new WNS protocol, even though it was included in the same

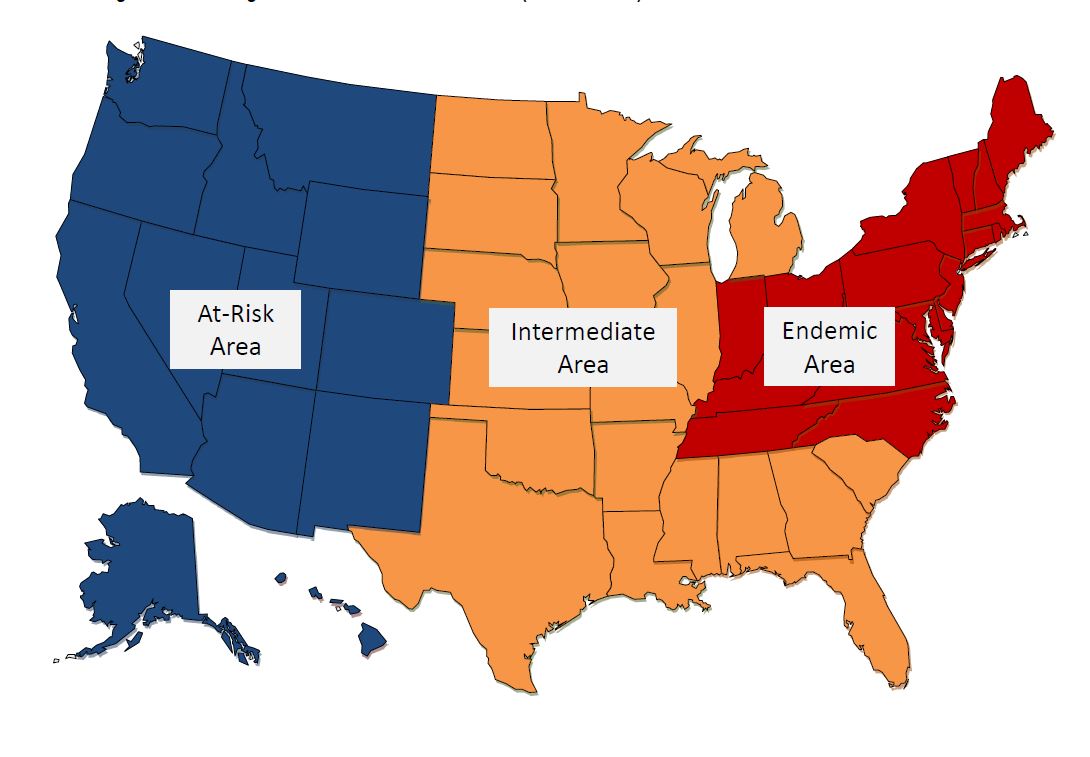

Sorry for the double dose of white nose syndrome (WNS) news, but I didn’t want this to get lost in yesterday’s post on the the new WNS protocol, even though it was included in the same  The National Wildlife Health Center (in Madison, Wisc., part of the US Geological Survey) has updated the Bat Submission Guidelines for the 2013/2014 white nose syndrome (WNS) surveillance season.These are the protocols that you, a state wildlife biologist, would use to submit a bat or other sample to the center for WNS diagnosis.

The National Wildlife Health Center (in Madison, Wisc., part of the US Geological Survey) has updated the Bat Submission Guidelines for the 2013/2014 white nose syndrome (WNS) surveillance season.These are the protocols that you, a state wildlife biologist, would use to submit a bat or other sample to the center for WNS diagnosis. A press release from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife was titled,

A press release from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife was titled,  – Ohio Department of Natural Resources is studying how and why bobcats have returned to the state, by tracking 21 collared bobcats,

– Ohio Department of Natural Resources is studying how and why bobcats have returned to the state, by tracking 21 collared bobcats,