In February, the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission collared 11 elk for a study in north-central Nebraska. There are a few more details in this brief KOLN-TV report.

In February, the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission collared 11 elk for a study in north-central Nebraska. There are a few more details in this brief KOLN-TV report.

A new elk study in Montana got more coverage. There, 45 cow and 20 bull elk were fitted with tracking collars. Five of those were traditional radio collars, the rest were GPS collars. The two year study will investigate elk movement patterns and food. Read about it in the Ravalli Republic.

In Wyoming, the concern is the potential to spread of chronic wasting disease at the 22 artificial feeding stations run by the state and one at the National Elk Refuge. Read the opinion piece in the Jackson Hole News & Guide, here.

An opinion piece that is getting a lot of buzz ran in the New York Times recently. It says that wolves did not fix the Yellowstone ecosystem by preying on elk and allowing aspen to grow. No, the article says, the Yellowstone ecosystem is broken, and mere wolves can’t fix it. Read the article in the New York Times, here.

Photo of bull elk courtesy US Fish and Wildlife Service

A study out of British Columbia, published in the

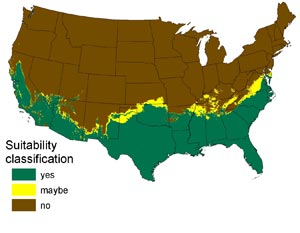

A study out of British Columbia, published in the  In 2008 the US Geological Survey published a report that said that the entire southern third of the United States could provide habitat for the invasive Burmese python that has been roiling the Florida Everglades ecoystem.

In 2008 the US Geological Survey published a report that said that the entire southern third of the United States could provide habitat for the invasive Burmese python that has been roiling the Florida Everglades ecoystem.