“The state’s moose population has been in decline for years but never at the precipitous rate documented this winter,” said Tom Landwehr, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources commissioner in a press release announcing the cancellation of Minnesota’s moose hunting season.

“The state’s moose population has been in decline for years but never at the precipitous rate documented this winter,” said Tom Landwehr, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources commissioner in a press release announcing the cancellation of Minnesota’s moose hunting season.

The commissioner noted that the state’s limited moose hunt was not the cause for the population’s decline.

The 2013 moose hunt was cancelled after aerial survey revealed the sharp drop in the moose population, the press release says. The survey was part of an on-going study of the state’s moose decline. (Previously covered here.)

The hunt’s cancellation was covered on NBC News’ national news. Read the article here.

Read the Minnesota DNR press release here.

Read more about the department’s moose mortality research project, on its webiste, here.

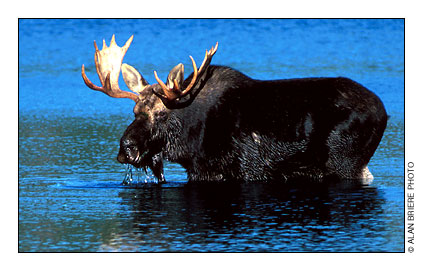

Photo: courtesy of Minnesota Dept. of Natural Resources

The the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources’ list of endangered, threatened and special concern species is due to get its first update since 1996,

The the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources’ list of endangered, threatened and special concern species is due to get its first update since 1996,