Plants, including crop plants such as alfalfa and tomatoes, may serve as a reservoir for the prions, or misfolded proteins, that cause chronic wasting disease in deer (as well as other prion diseases such as scrapie in sheep, and mad cow disease), reports WisconsinWatch after a careful reading of the The Wildlife Society conference program.

Plants, including crop plants such as alfalfa and tomatoes, may serve as a reservoir for the prions, or misfolded proteins, that cause chronic wasting disease in deer (as well as other prion diseases such as scrapie in sheep, and mad cow disease), reports WisconsinWatch after a careful reading of the The Wildlife Society conference program.

WisconsinWatch is produced by the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism. And they certainly investigated here.

Christopher Johnson, U.S. Geological Survey’s National Wildlife Health Center will present a talk on his research at the conference on October 7.

Oh, and Johnson found that the prions from plants were infectious when injected into mice.

I’m going to skip right over the scary prospect of plants as a reservoir for prion diseases and go right to the next point made in the WisconsinWatch article: this finding is not going to change the fact that the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources has pretty much given up on managing CWD in the state.

Johnson’s findings have not yet been published in a scientific journal, and it appears that the National Wildlife Health Center has not yet released a report or a press release on the research.

Find The Wildlife Society Conference abstract here.

Read the WisconsinWatch article here.

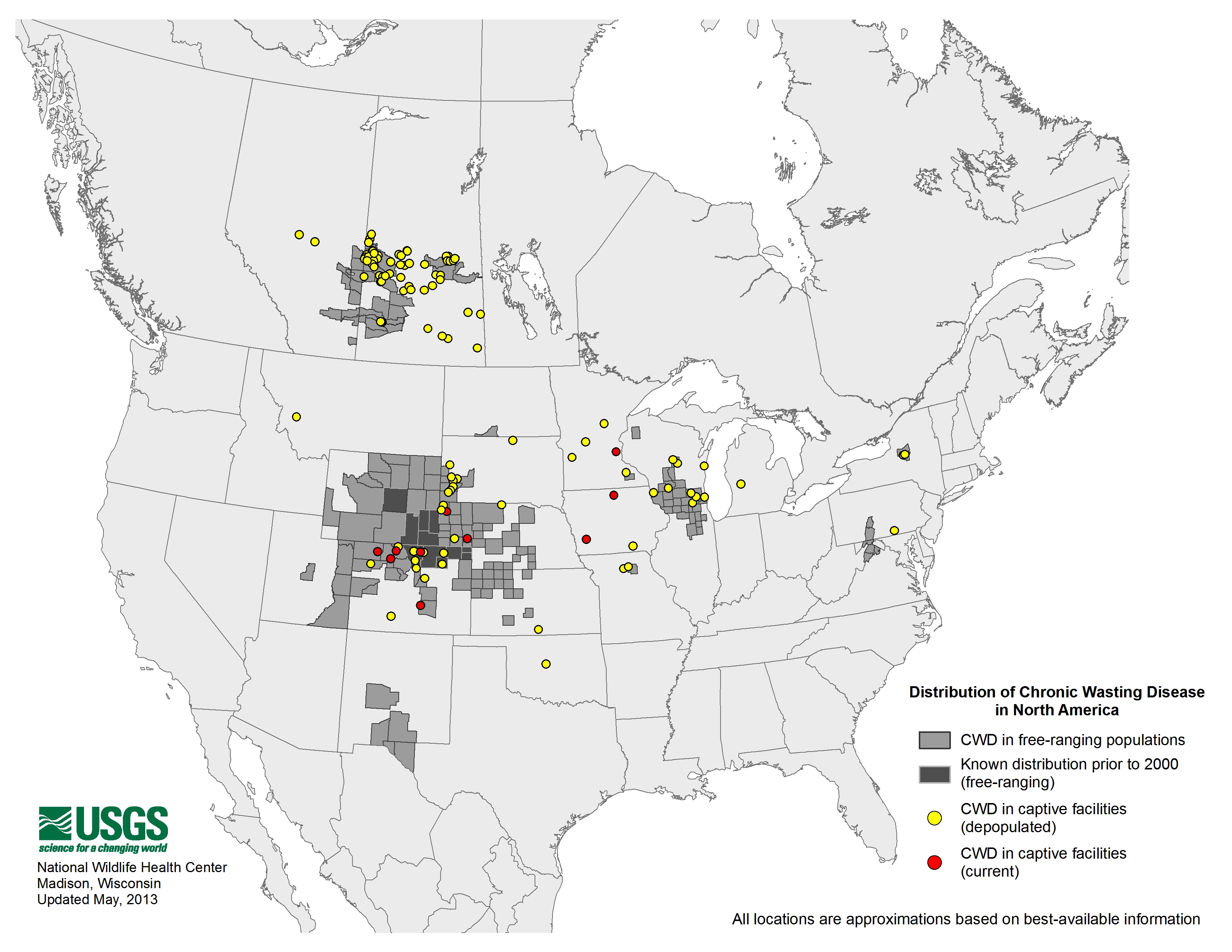

Map: Incidents of CWD, courtesy of USGS National Wildlife Health Center

About a third of the ponds in a Missouri study harbored chytrid fungus. A

About a third of the ponds in a Missouri study harbored chytrid fungus. A  Four new species of legless lizards have been discovered in California, joining the one species of legless lizard that was previously known in the state.

Four new species of legless lizards have been discovered in California, joining the one species of legless lizard that was previously known in the state. Illinois Department of Natural Resources furbearer biologist Bob Bluet told the

Illinois Department of Natural Resources furbearer biologist Bob Bluet told the

A new species of chytrid fungus has a different ecological niche than the one that has been wiping out amphibians all over the globe, says John Platt it

A new species of chytrid fungus has a different ecological niche than the one that has been wiping out amphibians all over the globe, says John Platt it  A press release from

A press release from  Sure, you know all about roads and wildlife, but roads are not the only place that wildlife and human infrastructure can do bad things to each other. Two recent stories point out some of the more unusual ways that wildlife influences modern life, and how our modern structures influence the survival of wildlife. (Although that sounds so serious. One of these stories is “cute,” and the other has been mostly reported as “cute.”)

Sure, you know all about roads and wildlife, but roads are not the only place that wildlife and human infrastructure can do bad things to each other. Two recent stories point out some of the more unusual ways that wildlife influences modern life, and how our modern structures influence the survival of wildlife. (Although that sounds so serious. One of these stories is “cute,” and the other has been mostly reported as “cute.”)