Non-native Burmese pythons are disrupting the south Florida ecosystem by devouring native wildlife. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) and its partners have used just about every tool in the box to try to control Burmese pythons in the state. Now it is trying one of the oldest wildlife control methods out there: competitive harvesting.

Non-native Burmese pythons are disrupting the south Florida ecosystem by devouring native wildlife. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) and its partners have used just about every tool in the box to try to control Burmese pythons in the state. Now it is trying one of the oldest wildlife control methods out there: competitive harvesting.

The FWC says, in a press release that the goal of the 2013 Python Challenge is to increase public awareness of this ecological threat. The contest will last a month, beginning January 12, 2013, and will award $1,500 dollars for the most Burmese pythons collected and $1,000 for the longest Burmese pythons in two categories of contestant, the general public and state python permit holders.

Contestants must complete on-line training to identify Burmese pythons and pay a $25 registration fee. The prize money, a Miami Herald article reports, will come from the entry fee and commission partners.

Now for a bit of editorializing: if it works, it will be the best $5,000 the commission never spent. But the risks are alarming. The on-line training appears insufficient (find it here). The better of the many possible poor outcomes is that the prize money won’t inspire enough people to scour south Florida’s public wetlands for what can be a dangerous snake. Part of the contest rules require that you own a GPS device or a smart phone to track your own movements during the python hunt, which is yet another barrier to participation.

At worst, greed and inexperience will mean people are hurt and native snakes slaughtered. Let’s hope FWC got it exactly right. If they did, it could provide a valuable model for other invasive species efforts.

Read the FWC press release here.

Read the Miami Herald article here.

Find the Python Challenge website here.

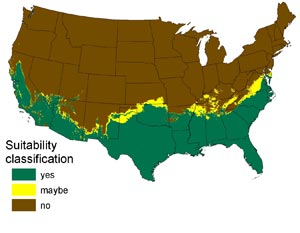

In 2008 the US Geological Survey published a report that said that the entire southern third of the United States could provide habitat for the invasive Burmese python that has been roiling the Florida Everglades ecoystem.

In 2008 the US Geological Survey published a report that said that the entire southern third of the United States could provide habitat for the invasive Burmese python that has been roiling the Florida Everglades ecoystem.

Last autumn, nine New England cottontails bred in captivity at the Roger Williams Park Zoo in Rhode Island were released inside a predator-proof fence enclosing one acre of the Ninigret National Wildlife Refuge, also in Rhode Island.

Last autumn, nine New England cottontails bred in captivity at the Roger Williams Park Zoo in Rhode Island were released inside a predator-proof fence enclosing one acre of the Ninigret National Wildlife Refuge, also in Rhode Island.