You may be using a smartphone to enter data in the field (hey, it beats lugging a laptop), and now the public can get in on wildlife conservation apps, too.

You may be using a smartphone to enter data in the field (hey, it beats lugging a laptop), and now the public can get in on wildlife conservation apps, too.

The National Wildlife Refuge System has been busy adding interactive smartphone applications. Patuxent Research Refuge, outside Washington, D.C. and Las Vegas National Wildlife Refuge in New Mexico are putting QR codes at trailheads. The Aransas Wildlife Refuge in Texas, and Great Meadows in Massachusetts, are putting QR codes on visitor brochures, kiosks, interpretive panels and printed trail maps.

That’s in addition to the app the system introduced last year, MyRefuge, featuring maps of scores of refuge recreation trails and other visitor attractions. Also last year, the system introduced the interactive iNature Trail at J.N. “Ding” Darling National Wildlife Refuge in Florida.

There’s more, and you can read about it in the National Wildlife Refuge System press release, here.

Access MyRefuge, here.

The BirdLog apps lets bird watchers (and researchers) enter data into eBird in the field using an iPhone or Android smartphone. An app for iPad is coming soon. A portion of the cost goes to Cornell Lab of O conservation activities.

Read the Cornell Lab of Ornithology release here.

The eBird press release is here.

Getting injured animals to wildlife rehabilitators and keeping the public safe as they try to assist injured wildlife can be difficult. It’s hard to be available 24-hours a day. In the Boulder, Colorado region a new web site and app, AnimalHelpNow, lets people report injured wildlife on their smartphones. The developers hope to have versions for other parts of the country soon.

Read (or listen) to the National Public Radio story on the app, here. Lots of links to follow to get the app and other information.

Finally, it’s not all sunshine and happiness is app-land. New apps that give Yellowstone visitors the locations of bears and other watchable wildlife have park advocates worried. The park’s bear jams are already dangerous, both as a travel hazard and because people get too close to the animals.

Read the article in USA Today.

Read the blog post in Field & Stream

Photo: A visitor prepares her smartphone to scan quick response (QR) codes along the iNature Trail at J.N. “Ding” Darling National Wildlife Refuge, FL

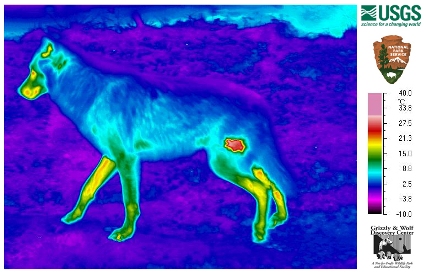

Do wolves and other large predators keep deer and other large herbivore populations in check, or is the food supply that really limits the herbivore population?

Do wolves and other large predators keep deer and other large herbivore populations in check, or is the food supply that really limits the herbivore population?

Which is more important, to save the global environment or to protect a particular ecosystem?

Which is more important, to save the global environment or to protect a particular ecosystem? The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) has proposed changes to the state’s endangered species list.

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) has proposed changes to the state’s endangered species list. A recent study of sage grouse in northeastern Wyoming says that the population there is just one severe weather event or West Nile outbreak away from extirpation. The study was conducted by three University of Montana wildlife biologists on behalf of the US Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

A recent study of sage grouse in northeastern Wyoming says that the population there is just one severe weather event or West Nile outbreak away from extirpation. The study was conducted by three University of Montana wildlife biologists on behalf of the US Bureau of Land Management (BLM).